02

Jun 2019

The End Of Whale Watching In Northern Norway?

Each winter, one of the most incredible events in the natural world unfolds in the Norwegian Arctic and for many it is the opportunity of a lifetime to witness it firsthand…

Sadly, due to the recent actions of some, this might not be possible for much longer and the days of seeing orcas and humpback whales in such a natural setting might be nearing its end, or at the very least become extremely restricted.

This article is aimed at anyone who is planning to, or will be joining a whale watching expedition in Northern Norway.

For decades it has been possible to visit Norway in order to join trips where you could see primarily sperm whales, orcas, and humpback whales. Until 2019 there was no real regulations controlling the practice of whale watching in Norway and the majority of operators were at the very least following guidelines set forth by the industry.

This could all change…

With discussions underway at government level with the eye on possible changes surrounding the whale watching industry (hopefully for the better of the animals), indications are the first lighter regulations (optimistically all that is needed) might be implemented towards the end of 2019. This comes in the wake of several foreign and ‘informal’ operators, as well as quite a few locally based operations having pushed the boundaries too far these last few years. The most notable of these events took place during the orca and humpback whale season, with the last season having been exceptionally bad. This included (but was not limited to):

- proximity to fishing operations without permission, resulting in unsafe situations and in some cases requiring the intervention by the coastguard.

- chasing / attempts at herding cetaceans,

- overcrowding

- no formal qualifications or experience

- unsafe and unethical practices

As a result, this coming winter could very well be the season deciding the future (or demise) of the whale watching industry in Northern Norway, particularly that segment which is geared towards orca and humpback whales during winter.

This would be a tragic outcome as a sustainable and ethical whale watching industry is completely possible and also serves to directly contribute to both education and conservation.

People are quick to lay the blame solely on the operators, however, the attitude of the clients they host is a major driving force behind many of these issues and also heavily influences the behavior of whoever is taking them out. In the age of ‘Instagram tourism’ this has become more relevant than ever…

Just One Example

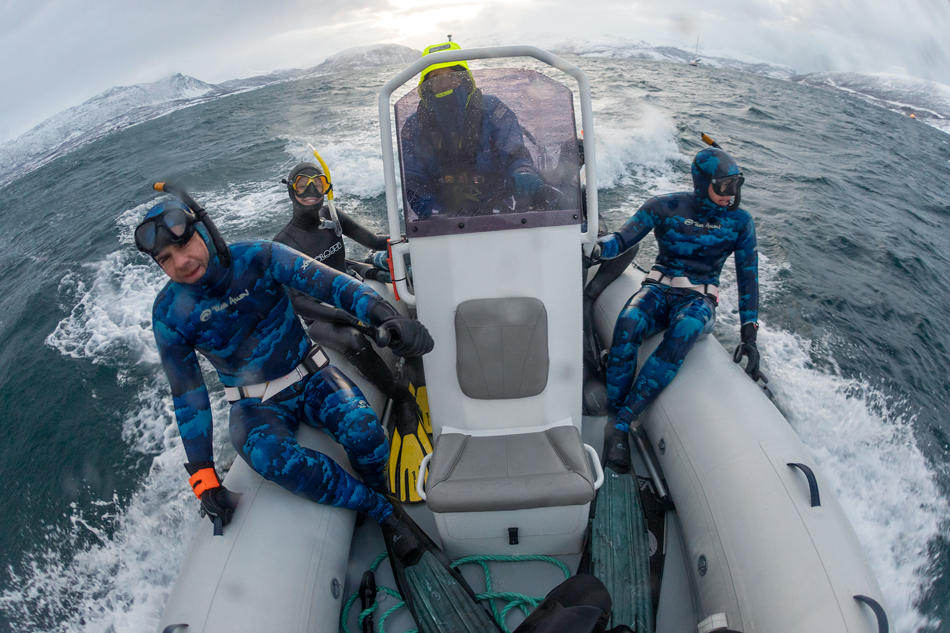

An extreme, real-world example could be seen last winter where a small fishing vessel took the opportunity to take snorkelers out to see orcas. In all likelihood, this was a Norwegian fisherman with little experience or training in the whale watching industry (although he has probably seen cetaceans hundreds of times while fishing) and therefore no idea of what ethical or safe practices are. The clients most likely negotiated a ‘cheap’ option to see the orcas.

Two snorkelers standing precariously over the propeller on the back of a fishing vessel flying a dive flag while they chase an orca pod (large male visible between the two vessels).

Using this one vessel as an example:

- The ‘approach’ method was to drive at top speed right onto, or in front of whatever cetaceans (mostly orcas) were around with no regard for other boat traffic or the behavior of the animals.

- The ‘clients’ were almost all dressed in dry suits, with fins etc and lined up on a small platform roughly 30cm wide at the vertical back of the boat right behind the propeller and rudder (not intended for snorkelers) .

- Once on top or right in front of the moving whales or orcas, these clients simply got a ‘go!’ from the captain or his assistant and jumped off while the boat was practically still running.

- From what we could see, these were inexperienced snorkelers who were struggling to move from point A to point B.

In this example, literally every single aspect of this is unethical, unsafe and in some cases illegal.

If you as the ‘client’ are comfortable with any aspect of this method of operating, you have NO business being at sea and no right to be anywhere near cetaceans or other ocean users.

At any point these clients could have said ‘Wait, this is really dangerous and we are harassing the animals.’.

As a result, one of two things would have happened – the skipper might have changed his way of operating to accommodate this shift in attitude (even if he does not understand the logic), or it would have been the end of their trip.

Either one of these options would have been better than the shocking behavior they pursued for the duration of their stay.

This is tragically not even close to some of the worst examples of what was seen the last two years…

Your role as the client

Some larger operators wreak even greater havoc over the duration of a season. This is due to the sizes of their fleet, how full they pack them, the types of fast boats they use and more importantly the way in which they choose to run their trips.

The goal of this article is to give anyone the basic knowledge to recognize either unsafe or unethical behavior and to encourage them to SPEAK UP! It is so common to hear people at the end of their trip complaining about the ‘dodgy’ operator they were with, yet no one ever challenges the people in charge or ‘worst case’, gets off the boat.

An orca pod with a young calf visible in the background.

Why do you want to go?

It all starts here and it is a simple question. What is your motivation for wanting to see orcas or humpback whales in Northern Norway (or wildlife anywhere) ?

Are you passionate about any of these animals? Do you have a love for nature and the outdoors as a whole? Maybe you are a serious, or even amateur wildlife photographer who simply wants to capture their beauty in such a wild setting?

These are the kind of people who deserves to have the chance to experience these animals in the wild on the animals terms and who surely has the moral and ethical sensibility to recognize unethical and unsafe situations.

If you have little interest in cetaceans and your main goal is to get awesome photos for Instagram or to film a videoblog about how daring you are to swim with orcas, then stay home or go do something else where hopefully you are not contributing to a bigger problem.

Do your research.

The internet is an incredible tool when it comes to researching potential businesses or products and operators are no exception. How do you find out what really goes on? Simple – ask the clients who have joined them before. This can be as easy as a short Facebook or Instagram message in reply to someone’s photo from their last trip.

Very often we hear of former clients getting messages from strangers asking them some of these simple questions:

- how was the trip and would they recommend the operator?

- was anything negative about their experience?

- Was the crew experienced and professional?

- did they feel like the animals were respected?

Do not simply rely on the reviews found on the actual page of the business or operator as these are very easy to falsify .

Some additional questions which you might want to ask or find the answers to include:

- Is this a registered operation or business in Norway? If not, you might be in for a nasty surprise when you arrive and new regulations prevent them from ‘operating’…

- What qualifications and experience do the guides and crew have?

- How much of an educational aspect is there to what the business / operator offers?

- What contribution do they make to the cetaceans they encounter (scientific, conservation etc)?

- Do they have formal standards on how they operate (relating to ethical and safe practices)?

- How many people do they take in one boat? This is CRUCIAL and will be discussed below.

- What requirements do they have for clients? For example – If it is an in-water expedition and the answer is ‘none’, start looking elsewhere.

At Sea

Be involved

Once you are with the operator or business you are joining, it is crucial to keep yourself up to speed on what is going on. There is nothing wrong with asking a simple question from time to time (although avoid doing it every 10 minutes!):

“What is the plan / What is happening?“

Whatever the reply is, it is crucial to match the reply to what you see is going on.

For example:

If the answer is “we are heading to a pod of orcas ‘over there’…” – have a look ‘over there’ and try to see what it is the crew are seeing.

- Is there already two or more other vessels in the area where the orcas are?

- Is there a working fishing trawler where the orcas are?

- Are the orcas in an area with heavy marine traffic (like the entrance to a harbor)?

‘Yes’ to any one of these questions should trigger instant concern and be followed up by more questions to the crew:

- “Are there not too many boats already around that pod?”

- “Do we have permission to approach that vessel?”

- “Is it not unsafe to dive at the harbor entrance?”

In this example, if the answer to any of these questions from the operator is ‘NO’, then it is time to speak up!

By failing to do so and simply shrugging your shoulders and silently objecting, you are directly contributing to the unethical and unsafe practices the whale watching industry and more importantly the animals are facing.

How to speak up

For many, confrontation is something they tend to avoid. The biggest problem is usually feeling like the only person who has to say something. This fear of confrontation easily leads to a lack of action and results in nothing being done about a serious problem.

So what is the best way to speak up against and confront unethical or unsafe behavior?

Do it as a group if possible. If you are uncomfortable saying something alone, go to the other guests and bring them up to speed on what is happening.

Using the previous example – even if you are confident enough to say something, it is still important to loop in the other guests and to make them understand why this is a bad situation. The important step is to actually SAY SOMETHING to the crew or operator. Simply complaining about it amongst yourselves but then still following the crews plan without saying anything to them does not make it OK.

If the crew gets the overwhelming feedback that their clients do not approve of their current plan of action, odds are very good that they will abandon it and change their approach to find something more suitable. This will hopefully also set the trend for the next days…

What to look out for / avoid.

(This will be kept brief and to the point in order to make it simple to follow.)

TOPSIDE

Fishing Boats or fishing activity (holding nets close to shore etc):

No whale watching boat (private or operator) has any business being near fishing activity. The only possible exception to this until recently was when the fishing vessel in question gave permission to a vessel with clear instructions such as distances to be kept, time allotted etc.

If you see a non-fishing vessel next to any type of fishing activity it is because:

- It is the Norwegian Coast Guard or Fiskeridirektoratet (fishery department) monitoring the activity

- They are there by permission (usually scientific) OR they have prior permission between the operator and fishing operation involved*

- They are there illegally and without permission

*with new regulations, this will most likely not be possible for much longer.

If the vessel you are on is neither of the examples listed above under 1 or 2, you are about to become number 3. If this is the case, you need to address your concern immediately and demand that you move away.

Overcrowding

A good approach to this is if at any point you are near cetaceans and there are more than two other vessels following the same group of animals, it is time to move away. Last winter as many as 26 vessels (including some jetskis!) were witnessed chasing one pod of orcas for as many as 4 hours! Do not even try to argue that ‘you were here first’ as sadly the attitude of most operators is to get to the front of the pack.

If at a distance you see maximum two vessels around a group of orcas or humpbacks, you need to hang back at least 300 to 500 meters and wait for your turn to approach. Depending on the situation, each vessel usually has around 30 minutes before having to leave the area. This needs to be kept within reason, so if there is a queue forming, it is also time to leave (the animals need a break as well!).

Racing / Competing

If you find yourself on a RHIB or vessel racing or competing against another vessel who will not stand down, it is time to leave. This behavior will carry on once you reach the cetaceans, which in turn results in a stressful and unsafe situation for them.

Boat traffic

If the cetaceans are in an area with heavy marine traffic such as a harbor entrance or busy channel, you need to move to a safe position and most definitely not attempt to enter the water.

Distance

Follow these guidelines. Anything closer is crossing the line.

Approach diagram presented in the national whale watching guidelines.

It is unacceptable to drive alongside a pod of orcas at arm’s reach (something we see every season)! If you would like to get ‘close up’ photos invest in a long telephoto lens and keep your distance.

Stalking

If the operator you are with uses the tactic of simply following other operators to find activity and then sending you out to the exact same spot where someone else is already having people in the water, you are now part of the problem.

A good example of this is a large foreign operation which sends several large ships to Norway and each of these can carry between 12 and 16 guests (22 with crew) and up to 3 large RHIBs per ship.*

(* paragraph updated – 4 June )

What we witnessed and experienced is that a different operator will have found a suitable, relaxed group of animals to interact with (or in past years have permission to be near fishing activity), when out of nowhere and without warning one or two RHIBs from these ships show up and drive right onto the same spot / people in the water and deposit anything from between 12 to 22 (or more) of their own clients in the water.

Shortly after having ‘chased’ away a pod of orcas, 11 snorkelers visible in shot with another 4 to 6 just outside frame. Shot taken as our group (4 people) were very quickly leaving the area having originally been there alone.

It is complete chaos and the RHIB drivers from these ships have zero regard for what is happening around them.

On several occasions we encountered ships/RHIBs like these and literally had to leave the area as quickly as possible for concern of our own safety as they are often unresponsive to confrontation of their behavior. Needless to say that it is not surprising to see the animals also move out as soon as this happens (see next section).

Again – do your research before booking.

APPROACH / IN-WATER

Group size and ratios

First off – cetaceans tend to avoid groups of people in the water (example above being a good one). The bigger the group of people in the water, the further they stay away. Worst case, they can potentially abandon baitballs or feeding opportunities when there are too many people crowding the area which is unacceptable.

Despite being at the top of the food chain, one of the reasons orcas are so successfully evolved and widespread can be attributed to their cautious behaviour.

If you are on a RHIB or diving boat and there are more than 6 other clients with you, with only one in-water guide present, something is very wrong (both ethically and in terms of safety). Add to this that most likely the majority of these people will have next to zero in-water experience, which is something you will realise very quickly…

To put it into perspective from a safety standpoint:

For a BEGINNER freediving or SCUBA course (using the equivalent of a IDSSC or WRSTC standards-based agency), the instructor to student ratio is 6:1 in open water. This is under controlled conditions with a trained instructor where students are always being supervised and are all at a level to be allowed to enter openwater.

As shocking as it might sound, the majority of the snorkel guides currently running trips in Northern Norway with orcas and humpback whales have no professional training (Instructor level or equivalent) and therefore despite also lacking the professional experience, have zero liability coverage (for which they are not eligible), zero training for in-water emergencies and also no legal basis to work as a ‘guide’.

To expect a person like this to keep an eye on anything from 8 to 12 or more people (this is not an exaggeration) in water which can be 200 to 300 meters deep, in arctic conditions with large marine life and other boat traffic etc around is absurd and incredibly unsafe.

Personally, I have been diving professionally for over a decade (Freediving Instructor Trainer, SCUBA Instructor and Commercial Diver) and have extensive experience diving with large marine life across the world. That being said, I would not feel confident to have more than 5 people in the water with me during an orca expedition in Norway, regardless of their prior experience. Five clients is really the upper limit of what can be considered a safe / manageable group and in some cases we have even reduced this ratio down to 1:4 (one professional guide supervising 4 guests).

This does not even take into account the assisted supervision we have at any given time from a quick response RHIB (always within seconds of the people in water) as well as the main diving vessel which is a bit further off.

Approach

How much thought and observation goes into the approach phase of an in-water interaction? How much of a briefing is there prior to every single in-water session? If the answer to these questions is almost nothing or zero then it is completely unsafe and unethical.

Just 6 simple rules to remember (and this does not even begin to delve into the topic of approach):

- Cetaceans do not like being approached head-on or directly from the back (either by boat or in-water). For the most part they do not like anything heading straight towards them from any side…

- Chasing ahead of cetaceans which are clearly moving/ underway and dumping clients into the water a short distance in front of them to get a quick look is unethical and unsafe. It is stressful to the animals (who 9 times out of 10 will just dive down anyway) and can also lead to them abandoning whatever they were busy with / heading towards (food source).

- If the cetacens(s) you are observing is making deliberate turns away from you, it is time to leave.

- Approaching any marine life as a line formation or group will most likely result in them leaving the area. Even 20 orcas will use caution and move away when they see 8 people splashing and kicking towards them. One more reason why small groups is a must.

- Is there already another boat following the same pod? Then it is time to leave. Animals should always feel like they have several options to turn away, which becomes less likely when they have multiple vessels following them from several sides.

- Did the guide give a clear briefing immediately before entering the water on the plan for the current situation (buddy pairs, approach plan, clear instructions, limitations, safety concerns, collection plan, time limit etc)? If not, DO NOT ENTER THE WATER.

In-Water

Again – just a very brief list of simple rules and points to look out for and follow:

- Never enter the water unsupervised

- Be sure you are visible (especially to boat traffic and your topside supervision).

- Always stay with a buddy. If you find yourself completely isolated, it is time to get back to your group or out of the water as quickly as possible.

- Do not ever attempt to touch a cetacean.

- Respect distances to animals, people, boats and activity as set by your guide / crew or by local regulations and guidelines

- If you see anything out of place or witness unsafe or unethical behavior, notify the crew immediately and get out.

Bait Balls (Carousel feeding)

Undoubtedly one of the most impressive spectacles each season and something not everyone is fortunate to witness. Herring baitballs can be smaller than 5 meters in diameter with only 3 or more orcas ‘working’ it, or be a seemingly never-ending ball of fish up to 15 meters deep and wider than the eye can see, with several pods of orcas and multiple humpback whales feeding at the same time.

With orcas performing devastating tail slaps while humpback whales appears from below at break neck speeds, surging towards the surface with open mouths in a blink of an eye (we have witnessed as many as 9 at a time!), this is also one of the situations which poses the biggest threat to in-water users if not properly briefed or following proper guidelines.

An example of one of the most shocking social media posts we saw this last winter was from a tourist as a ‘thank you’ to an operator. It was a series of photos from inside a school of herring, including one of an orca emerging from a wall of during a carousel feeding event with a caption along the lines of:

“dropped into the middle of a baitball and enjoyed a herring massage as orcas fed all around me 💕”

For anyone who has any experience with carousel feeding, this description should turn your blood to ice. If you are at the surface and literally getting ‘massaged’ by herring and entirely surrounded by them, you are in one of the most dangerous positions possible. Clearly the person who wrote this knew no better and had no idea how dangerous the situation was that she was in, but for the operator to have allowed this is inexcusable.

To cover all the do’s and don’t’s of carousel feeding is a presentation in itself (which we do cover with all guests), but these are the most basic rules to follow:

- NEVER place yourself on top of or anywhere inside of a baitball. You should always be on the outside (easy to see as it represents the sides of a ball or wall). If you see herring all around you, you are in a very unsafe position.

- If the baitball moves around you (and it can happen), swim towards the outside as quickly as you can. Here your guide should have the experience and control to direct you.

- Do not touch or play with any stunned herring

- Do not swim directly at any animal which is feeding (they will leave the food)

- Keep a reasonable distance from the baitball as not to disturb it. People can disrupt the shape of the ball and cause the orcas to abandon it

- If you see one or more humpback whales in the general area (even if it is 50 meters away), notify the others in your group and keep your distance from the ball. Odds are high that the next time you see them will be when they are ‘breach feeding’ through the ball in the blink of an eye.

- Respect time limits. It might be one of the greatest events in the natural world, but you have no right to spend an hour disrupting it with your presence.

Summary

There are so many facets to running an ethical and safe operation and preparing guests in order to have the best possible experience. That being said, it all starts with getting individuals with the right mindset and attitude as guests and preparing them for what they are going to encounter.

The current challenges being faced by the cetaceans in Northern Norway as well as the whale watching operators who are striving to run ethical operations can be largely eliminated by proper and fair regulations, but also by the actions and informed decisions of clients.

So in closing – if you are planning on joining a whale watching expedition in Northern Norway, please do your research first and once there, do your best to at the very minimum stand up for what you believe is right and more importantly is in the interest of the animals we are fortunate to encounter.

– UPDATE –

In light of the response this article has generated, it is important to point out that there are thankfully several ‘serious’ operators in Norway, many of which I am happy to stand behind and that the problems (and images) presented here are extreme examples witnessed over several months, spread over the last two years.

Although more common than previous years, these situations are not ‘the rule’ or a daily occurrence as some people have tried to incorrectly portray by using my content.

As mentioned, the hope is that excessive regulations are not necessary and that by simply ‘regulating’ the industry to a point where responsible and ethical operations and ocean users can continue as they have in previous years, is all that is needed.